Still confused about cancer screening, and whether it's right for you?

I've posted a lot of information in this blog, some of it more technical, but most I've tried to make as digestible as possible.

But what if you're still not sure whether screening is the right choice for you? After all, this is just an internet blog...

I can help!

Here is a very simple form that you can print out and take along to your doctor or nurse, and ask them to fill out for you. In order for you to be able to give informed consent, they should be able to give you the information required. After all, nobody can give informed consent, without being informed!

So, with this completed by your doctor or nurse, you can then decide for yourself whether the benefits of screening (the difference between the top 2 boxes, and ultimately the last box), and the risks of screening (the 3rd and 4th boxes).

If your doctor or nurse cannot give you this information, I would strongly advise refusing to be screened until they can provide it. If they don't know the risks and benefits, then they really shouldn't be offering the screening.

I hope this helps someone to make an informed choice!

Cancer Screening Facts

Saturday, 9 February 2019

Monday, 4 February 2019

Cervical screening in women under the age of 25. Worth it?

I often see and hear younger women upset that they "cannot get their smear test" until they turn 25.

The fervour in the media, from charities with their own agendas, and sadly, from uninformed celebrities, regarding cervical screening has led to younger women wondering why they cannot be screened, and worried that they are at risk of cervical cancer.

When cervical screening was introduced in 1988, the age from which screening was offered was set at 20. This was "largely based on available data at the time". (Source: https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2014/04/28/what-is-the-right-age-for-cervical-screening/)

Of course the UK had no cervical screening programme before this, so quite where this data came from is unclear.

In 2003, a group of expert clinicians and scientists, the Advisory Committee on Cervical Screening (ACCS), was asked to review the age from which cervical screening should be offered.

They analysed the evidence that was available from the 15 years of data now available from the active screening programme, and found that levels of abnormal cell changes were very high in the 20 to 25 year old population, however cervical cancer in this age group was actually very low indeed. Within this age group that cervix is still maturing, and the "abnormal cells" are actually very normal in this group.

So, many young women were undergoing unnecessary screening, testing and surgical treatment for no benefit, and indeed, at great risk of harm.

The age was reviewed again in 2009, and ACCS reaffirmed that screening the under-25s was harmful, and offered no benefit.

In short, all the experts agree that the risk of cervical cancer in the under-25's is so rare, and the risk of over-treatment so high, that it would cause more harm than good.

To look at the incidence by age shows that the under-25's have less risk of cervical cancer than the over 80's:

The highest risk is in the 25-29 age group, although even at this age, the risk of developing cervical cancer is only ~21 women per 100,000, or 0.021% when expressed as a percentage.

Cervical cancer is low risk disease in all cases, and in the under-25's, the risk is lower still.

Screening the under-25's can do nothing but harm. That is why they are not offered screening anymore.

The fervour in the media, from charities with their own agendas, and sadly, from uninformed celebrities, regarding cervical screening has led to younger women wondering why they cannot be screened, and worried that they are at risk of cervical cancer.

When cervical screening was introduced in 1988, the age from which screening was offered was set at 20. This was "largely based on available data at the time". (Source: https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2014/04/28/what-is-the-right-age-for-cervical-screening/)

Of course the UK had no cervical screening programme before this, so quite where this data came from is unclear.

In 2003, a group of expert clinicians and scientists, the Advisory Committee on Cervical Screening (ACCS), was asked to review the age from which cervical screening should be offered.

They analysed the evidence that was available from the 15 years of data now available from the active screening programme, and found that levels of abnormal cell changes were very high in the 20 to 25 year old population, however cervical cancer in this age group was actually very low indeed. Within this age group that cervix is still maturing, and the "abnormal cells" are actually very normal in this group.

So, many young women were undergoing unnecessary screening, testing and surgical treatment for no benefit, and indeed, at great risk of harm.

The age was reviewed again in 2009, and ACCS reaffirmed that screening the under-25s was harmful, and offered no benefit.

In short, all the experts agree that the risk of cervical cancer in the under-25's is so rare, and the risk of over-treatment so high, that it would cause more harm than good.

To look at the incidence by age shows that the under-25's have less risk of cervical cancer than the over 80's:

(Source: https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/cervical-cancer/incidence#heading-One)

The highest risk is in the 25-29 age group, although even at this age, the risk of developing cervical cancer is only ~21 women per 100,000, or 0.021% when expressed as a percentage.

Cervical cancer is low risk disease in all cases, and in the under-25's, the risk is lower still.

Screening the under-25's can do nothing but harm. That is why they are not offered screening anymore.

Wednesday, 30 January 2019

Cervical Cancer and HPV. Is vaccination the answer?

What causes cervical cancer? Why do some people get it, and not others?

The answer is HPV. HPV infection causes more than 99% of cervical cancer cases. (Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22727241)

HPV (Human Papillomavirus) comes in many different forms. 40 of them are sexually transmitted, and of those, only some cause cervical cancer. These are known as the high-risk sub types.

In 2005 the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) working group classified HPV types into the following grades:

(Source: International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; Human Papillomaviruses, Volume 90. Lyon, France; 2007;255-313)

Currently, it is accepted that the following 14 HPV genotypes are the high-risk or oncogenic sub types and have caused invasive cervical cancer: 16, 18 ,31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68.

The NHS vaccination program for HPV uses the GARDASIL vaccine, which protects again HPV 16 & 18, which cause 70% of cervical cancer cases. (Source: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/19033)

It also protects against HPV 6 & 11, which cause genital warts, but are not linked to cancer.

A newer vaccination, GARDASIL 9, is effective against HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58, which cause an estimated 90% of cervical cancers.

It's also important to consider the long-term safety of vaccination, and it has been shown that HPV vaccination is about as safe as other childhood vaccinations, although with an increased risk of syncope (fainting) at time of vaccination. (Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4262378/)

Also important to note is that HPV infections are normally cleared by the immune system within 2 years. Rarely, an HPV infection can persist, and if it remains active for up to 15-20 years, it can cause cell changes that lead to cervical cancer developing. (Source: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer)

So, the more high-risk HPV sub types that we can vaccinate against, the more protection is conferred. If (when?) we can vaccinate against all high-risk HPV sub types, we should in theory be able to eradicate cervical cancer entirely. (along with anal cancer, and some head & neck cancers)

So, should you, or your children accept the offered HPV vaccination?

As always, it's entirely up to you. The evidence suggests that the vaccination is both safe, and effective at preventing cervical cancer, but as always, make the decision knowing all of the evidence.

The answer is HPV. HPV infection causes more than 99% of cervical cancer cases. (Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22727241)

HPV (Human Papillomavirus) comes in many different forms. 40 of them are sexually transmitted, and of those, only some cause cervical cancer. These are known as the high-risk sub types.

In 2005 the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) working group classified HPV types into the following grades:

- Grade 1 (carcinogenic to humans): HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59

- Grade 2A (probably carcinogenic to humans) HPV 68

- Grade 2B (possibly carcinogenic to humans) 26, 53, 66, 67, 70, 73, 82, 30, 34, 69, 85, and 97

- Grade 3 (not carcinogenic) 6, 11

(Source: International Agency for Research on Cancer. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans; Human Papillomaviruses, Volume 90. Lyon, France; 2007;255-313)

Currently, it is accepted that the following 14 HPV genotypes are the high-risk or oncogenic sub types and have caused invasive cervical cancer: 16, 18 ,31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68.

The NHS vaccination program for HPV uses the GARDASIL vaccine, which protects again HPV 16 & 18, which cause 70% of cervical cancer cases. (Source: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/19033)

It also protects against HPV 6 & 11, which cause genital warts, but are not linked to cancer.

A newer vaccination, GARDASIL 9, is effective against HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58, which cause an estimated 90% of cervical cancers.

It's also important to consider the long-term safety of vaccination, and it has been shown that HPV vaccination is about as safe as other childhood vaccinations, although with an increased risk of syncope (fainting) at time of vaccination. (Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4262378/)

Also important to note is that HPV infections are normally cleared by the immune system within 2 years. Rarely, an HPV infection can persist, and if it remains active for up to 15-20 years, it can cause cell changes that lead to cervical cancer developing. (Source: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/human-papillomavirus-(hpv)-and-cervical-cancer)

So, the more high-risk HPV sub types that we can vaccinate against, the more protection is conferred. If (when?) we can vaccinate against all high-risk HPV sub types, we should in theory be able to eradicate cervical cancer entirely. (along with anal cancer, and some head & neck cancers)

So, should you, or your children accept the offered HPV vaccination?

As always, it's entirely up to you. The evidence suggests that the vaccination is both safe, and effective at preventing cervical cancer, but as always, make the decision knowing all of the evidence.

Monday, 28 January 2019

Treatment for abnormal cervical screening results; the risks and benefits.

If you've made an informed choice to participate in cervical screening, then it's likely at some point that you'll have an "abnormal result", which might leave you feeling scared, anxious, and worried about getting cancer.

In fact 1 in 20 women will get an abnormal result (5%), whilst only 1 in 2000 will have cancer found (0.05%).

(source: https://www.bsccp.org.uk/women/frequently-asked-questions).

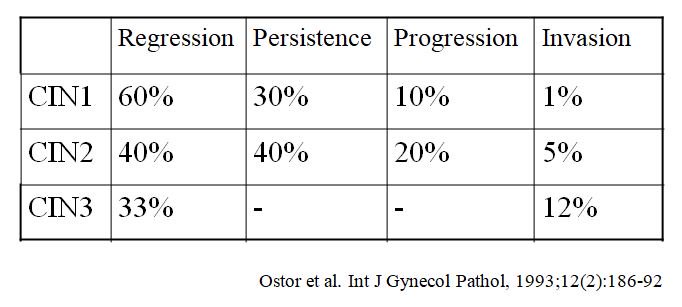

These abnormal results are due to the detection of cells which have changes to their normal appearance under a microscope. They aren't cancer, but there is a chance that they could become cancerous. Here are the risks of that happening:

There are 3 levels of "abnormality", CIN1, 2 & 3, with CIN3 being the most likely to progress to cancer (invasion). Although even at CIN3, we can see that the risk is just 12%.

Having had an abnormal result, you have some options available to you. With CIN1 you would almost always "wait and watch", as the abnormal changes are caused by HPV infection, a sexually transmitted virus, which in most cases the body will clear by itself.

If you have CIN2 or 3, whilst the risk of cancer is still relatively low, you will likely be offered treatment.

The mainstay of treatment for CIN2 & 3 is a procedure called LEEP (Loop electrosurgical excision procedure), also known as LLETZ (Large loop excision of the transformation zone).

This involves taking an electrically charged wire loop to remove a chunk of the cervix where the abnormal cells are. It looks like this:

There's also a video showing the procedure on YouTube (viewer discretion is advised): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z6_Yb8ad_9g

So, the idea is that they cut away the chunk of your cervix with the abnormal cells (which are in the top layer of skin, but for some reason they take a huge chunk away!), and you go merrily about your life with no more worries of cancer. Sounds good right!

Sadly it's not always that way. As with all procedures, there are risks. Some physical, some mental, often both.

LEEP & LLETZ (they're the same thing) potential complications include:

Infections of the cervix can occur, and occasionally

infection may be introduced into the uterus, Fallopian tubes or other pelvic organs. This may require treatment with antibiotics and further treatment.

In fact 1 in 20 women will get an abnormal result (5%), whilst only 1 in 2000 will have cancer found (0.05%).

(source: https://www.bsccp.org.uk/women/frequently-asked-questions).

These abnormal results are due to the detection of cells which have changes to their normal appearance under a microscope. They aren't cancer, but there is a chance that they could become cancerous. Here are the risks of that happening:

Having had an abnormal result, you have some options available to you. With CIN1 you would almost always "wait and watch", as the abnormal changes are caused by HPV infection, a sexually transmitted virus, which in most cases the body will clear by itself.

If you have CIN2 or 3, whilst the risk of cancer is still relatively low, you will likely be offered treatment.

The mainstay of treatment for CIN2 & 3 is a procedure called LEEP (Loop electrosurgical excision procedure), also known as LLETZ (Large loop excision of the transformation zone).

This involves taking an electrically charged wire loop to remove a chunk of the cervix where the abnormal cells are. It looks like this:

There's also a video showing the procedure on YouTube (viewer discretion is advised): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z6_Yb8ad_9g

So, the idea is that they cut away the chunk of your cervix with the abnormal cells (which are in the top layer of skin, but for some reason they take a huge chunk away!), and you go merrily about your life with no more worries of cancer. Sounds good right!

Sadly it's not always that way. As with all procedures, there are risks. Some physical, some mental, often both.

LEEP & LLETZ (they're the same thing) potential complications include:

infection may be introduced into the uterus, Fallopian tubes or other pelvic organs. This may require treatment with antibiotics and further treatment.

Bleeding could occur from the cervix and may require a

blood transfusion, a return to the operating room or other

measures, such as vaginal packing, to control the bleeding.

Damage and narrowing of the cervix could occur which

can cause painful periods and difficulty in labour.

Complete closure of the cervical canal, which can cause

difficulty in having a period, pelvic pain, infertility and

difficulty obtaining a pap smear. The cervical canal might

require dilatation under anaesthetic and on some occasions

it may require having a hysterectomy (removal of uterus).

The cervix may be weakened which can lead to early

pregnancy loss and the occasional need to strengthen

the cervix during a pregnancy by the insertion of a special

stitch (cervical cerclage). The risk of preterm labour is also

increased. Women who have had a prior LLETZ procedure

may have to have their cervix length measured regularly by

ultrasound during pregnancy to ensure it is not shortening

or opening too early.

Blood clot in the leg causing pain and swelling. In rare

cases, part of the clot may break off and go to the lungs.

Small areas of the lung can collapse, increasing the

risk of chest infection. This may need antibiotics and

physiotherapy.

Heart attack or stroke could occur due to the strain on

the heart.

Damage to surrounding organs such as bladder, rectum

etc. and further surgery may be required to rectify this.

Subsequent infertility.

Miscarriage or premature labour can occur, usually from

12 weeks onward in future pregnancies, as a result of

weakness of the cervix. This is relatively more common if

this procedure has to be done more than once .

Hysterectomy (removal of uterus) if bleeding is unable to

be controlled.

(Source: https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0035/147887/obst_gyna_23.pdf)

Wow, that's a long list! So those are the official complications, as found in the consent form in the source link above.

So is that all we have to worry about? Looking at women's stories in the media and online, it seems not, sadly.

Women have complained of suffering from weakened stomach muscles, a loss of libido (desire for sex), loss of orgasm and painful sex.

(Source: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-5960067/The-women-say-treatment-smear-test-RUINED-sex-lives.html)

So, a treatment which isn't even for cancer, but rather some cell changes that just might become cancer, could leave you infertile, in constant pain, lacking a sex drive, or orgasmic ability.

Should you accept this treatment?

That's really up to you. There is a risk of cancer, but there's also a chance that you'll be absolutely fine.

But if you do, do so knowing all the risks and benefits. This information is not always given to women, and it should be.

Monday, 17 December 2018

Bowel Cancer Screening

Nobody wants to be diagnosed with bowel (colorectal) cancer, it's a nasty disease.

Thankfully symptoms (https://www.bowelcanceruk.org.uk/about-bowel-cancer/symptoms/) often present early, and with early treatment, the outcomes are generally good, around 92% for Stage I survival after 5 years. (source: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html)

But, of course, there's a screening test. FOBT has long been used for this purpose. Well, how good is this screening test? Fortunately, to stop me boring you with all the detail, the Harding Center for Risk Literacy has done all the hard work for me:

So, what does this tell us? In 1000 people without screening, 10 people will be diagnosed with advanced colorectal cancer, and 7 of them will die from it.

In 1000 people who did have screening, 9 will be diagnosed correctly, but 6 will still die from colorectal cancer. However, 6 people will be told that they don't have cancer, when in fact they do, delaying treatment that could be disastrous.

So screening saved 1 life, but potentially killed another 6 people by missing their cancer.

They screen, because they can. That doesn't mean that it's good for your health to accept the invitation.

Promptly investigating symptoms is, in my opinion, a far better choice than bowel screening.

Thankfully symptoms (https://www.bowelcanceruk.org.uk/about-bowel-cancer/symptoms/) often present early, and with early treatment, the outcomes are generally good, around 92% for Stage I survival after 5 years. (source: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html)

But, of course, there's a screening test. FOBT has long been used for this purpose. Well, how good is this screening test? Fortunately, to stop me boring you with all the detail, the Harding Center for Risk Literacy has done all the hard work for me:

So, what does this tell us? In 1000 people without screening, 10 people will be diagnosed with advanced colorectal cancer, and 7 of them will die from it.

In 1000 people who did have screening, 9 will be diagnosed correctly, but 6 will still die from colorectal cancer. However, 6 people will be told that they don't have cancer, when in fact they do, delaying treatment that could be disastrous.

So screening saved 1 life, but potentially killed another 6 people by missing their cancer.

They screen, because they can. That doesn't mean that it's good for your health to accept the invitation.

Promptly investigating symptoms is, in my opinion, a far better choice than bowel screening.

Monday, 10 December 2018

NHS breast screening - Helping you decide

It quite a nice pink leaflet really, despite what's inside.

The problem is, that whilst it gives some simplified information, it doesn't give women the whole picture. There's not enough information to make in informed choice.

The NHS breast screening program was introduced in 1988 (strangely at the same time as cervical screening was introduced, which is an interesting coincidence).

How has the incidence of breast cancer changed since it was introduced?

Let's have a look at the data:

So screening doesn't affect how many women get breast cancer, as it can't look for "pre-cancerous" cells, it can only detect cancer once it has developed to some degree. It doesn't stop you from getting breast cancer.

So what was the effect on mortality from breast cancer? Does finding it early increase your chance of survival?

(Source: Cancer Research UK)

Ok, so the short answer is yes. After 1988 there is a clear drop in the number of women dying from breast cancer. It looks impressive as a graph, but let's look at the absolute risk of dying from breast cancer.

Around 1988, 60 women per 100,000 were dying of breast cancer. That's a 0.06% risk. By 2016, that risk has declined to ~34 women per 100,000. That's a 0.034% risk. So the actual decline in risk is 0.026%.

The decline is of course due to early detection and treatment, so what's the harm?!

That is, of course, a good question.

As you'll see in my earlier posts, all screening tests have a sensitivity level, and a specificity level. These numbers indicate the chance of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives.

Instead of crunching the numbers myself, I'll post a figure from a respected medical journal:

(Source: https://breast-cancer-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13058-015-0525-z#Fig1)

So this shows that for every 1000 women screened over the course of 20 years, 200 will be incorrectly told that they have breast cancer, of those 200, 20 will also have a biopsy to rule out cancer.

3 will develop cancer anyway, either because it was missed in the mammogram, or a fast growing tumour grew between screening periods enough to cause symptoms (interval cancers). A previously negative mammogram might also cause women to assume they're "safe" and ignore symptoms.

15 out of the 1000 women will actually be treated for cancer that they don't have, with lumpectomy, mastectomy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy etc.

Only 2 breast cancer deaths will be prevented per 1000 women, but overall no deaths will be prevented. Why? Treating breast cancer, can cause other issues like heart problems, and you're killed by the treatment.

Another issue is that of finding cancers that, whilst definitely cancers, wouldn't cause you problems in your lifetime.

This is especially true for older women who would likely die from another condition (heart disease etc.) long before their breast cancer would kill them.

So, should you get screened? As always, it's your choice!

Inform yourself of the benefits, and risks, and make the decision based on your own personal situation.

The problem is, that whilst it gives some simplified information, it doesn't give women the whole picture. There's not enough information to make in informed choice.

The NHS breast screening program was introduced in 1988 (strangely at the same time as cervical screening was introduced, which is an interesting coincidence).

How has the incidence of breast cancer changed since it was introduced?

Let's have a look at the data:

So screening doesn't affect how many women get breast cancer, as it can't look for "pre-cancerous" cells, it can only detect cancer once it has developed to some degree. It doesn't stop you from getting breast cancer.

So what was the effect on mortality from breast cancer? Does finding it early increase your chance of survival?

Ok, so the short answer is yes. After 1988 there is a clear drop in the number of women dying from breast cancer. It looks impressive as a graph, but let's look at the absolute risk of dying from breast cancer.

Around 1988, 60 women per 100,000 were dying of breast cancer. That's a 0.06% risk. By 2016, that risk has declined to ~34 women per 100,000. That's a 0.034% risk. So the actual decline in risk is 0.026%.

The decline is of course due to early detection and treatment, so what's the harm?!

That is, of course, a good question.

As you'll see in my earlier posts, all screening tests have a sensitivity level, and a specificity level. These numbers indicate the chance of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives.

Instead of crunching the numbers myself, I'll post a figure from a respected medical journal:

(Source: https://breast-cancer-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13058-015-0525-z#Fig1)

So this shows that for every 1000 women screened over the course of 20 years, 200 will be incorrectly told that they have breast cancer, of those 200, 20 will also have a biopsy to rule out cancer.

3 will develop cancer anyway, either because it was missed in the mammogram, or a fast growing tumour grew between screening periods enough to cause symptoms (interval cancers). A previously negative mammogram might also cause women to assume they're "safe" and ignore symptoms.

15 out of the 1000 women will actually be treated for cancer that they don't have, with lumpectomy, mastectomy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy etc.

Only 2 breast cancer deaths will be prevented per 1000 women, but overall no deaths will be prevented. Why? Treating breast cancer, can cause other issues like heart problems, and you're killed by the treatment.

Another issue is that of finding cancers that, whilst definitely cancers, wouldn't cause you problems in your lifetime.

This is especially true for older women who would likely die from another condition (heart disease etc.) long before their breast cancer would kill them.

So, should you get screened? As always, it's your choice!

Inform yourself of the benefits, and risks, and make the decision based on your own personal situation.

Tuesday, 4 December 2018

Survivor Fever

Survivor Fever. Yes, I made up the name; it seemed to fit.

What am I talking about?

Well, it's a phenomenon that happens all to often in screening.

Let's say that you go for a screening test, and you get back a negative result. You're happy, relieved, and want others to also be screened, to know that they're also "safe".

Then there are those that receive a positive result. Abnormal cells, we'd better act now. So they get their abnormal cells treated, which probably wasn't necessary (see previous posts), but now they feel that they had a lucky escape; evaded cancer. And so they become vehement advocates for screening; "It could save your life! It saved mine!".

The reality is that screening, whilst it can detect a proportion of cancer, or precancerous conditions, falsely diagnoses a magnitude more, and that, in itself, leads to a large population of people believing that screening is "important".

These people, due to the failings of both government, and charities, are not fully informed of the risks, benefits, and harms of screening. In fact, some of the loudest proponents of screening are those that have been harmed. People with minor, harmless, changes to their cells, that are treated needlessly, who end up thinking that they have been saved from cancer.

We all need to educate ourselves, read the numbers, make an informed decision, and not follow blindly like lemmings off a cliff.

What am I talking about?

Well, it's a phenomenon that happens all to often in screening.

Let's say that you go for a screening test, and you get back a negative result. You're happy, relieved, and want others to also be screened, to know that they're also "safe".

Then there are those that receive a positive result. Abnormal cells, we'd better act now. So they get their abnormal cells treated, which probably wasn't necessary (see previous posts), but now they feel that they had a lucky escape; evaded cancer. And so they become vehement advocates for screening; "It could save your life! It saved mine!".

The reality is that screening, whilst it can detect a proportion of cancer, or precancerous conditions, falsely diagnoses a magnitude more, and that, in itself, leads to a large population of people believing that screening is "important".

These people, due to the failings of both government, and charities, are not fully informed of the risks, benefits, and harms of screening. In fact, some of the loudest proponents of screening are those that have been harmed. People with minor, harmless, changes to their cells, that are treated needlessly, who end up thinking that they have been saved from cancer.

We all need to educate ourselves, read the numbers, make an informed decision, and not follow blindly like lemmings off a cliff.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Still confused about cancer screening, and whether it's right for you?

Still confused about cancer screening, and whether it's right for you? I've posted a lot of information in this blog, some of it m...

-

If you've made an informed choice to participate in cervical screening, then it's likely at some point that you'll have an ...

-

It quite a nice pink leaflet really, despite what's inside. The problem is, that whilst it gives some simplified information, it doesn...

-

Sounds familiar, right? It’s the title of the little green information leaflet that is sent out with your invitation to attend cervical sc...