Nobody wants to be diagnosed with bowel (colorectal) cancer, it's a nasty disease.

Thankfully symptoms (https://www.bowelcanceruk.org.uk/about-bowel-cancer/symptoms/) often present early, and with early treatment, the outcomes are generally good, around 92% for Stage I survival after 5 years. (source: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/colon-rectal-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html)

But, of course, there's a screening test. FOBT has long been used for this purpose. Well, how good is this screening test? Fortunately, to stop me boring you with all the detail, the Harding Center for Risk Literacy has done all the hard work for me:

So, what does this tell us? In 1000 people without screening, 10 people will be diagnosed with advanced colorectal cancer, and 7 of them will die from it.

In 1000 people who did have screening, 9 will be diagnosed correctly, but 6 will still die from colorectal cancer. However, 6 people will be told that they don't have cancer, when in fact they do, delaying treatment that could be disastrous.

So screening saved 1 life, but potentially killed another 6 people by missing their cancer.

They screen, because they can. That doesn't mean that it's good for your health to accept the invitation.

Promptly investigating symptoms is, in my opinion, a far better choice than bowel screening.

Monday, 17 December 2018

Monday, 10 December 2018

NHS breast screening - Helping you decide

It quite a nice pink leaflet really, despite what's inside.

The problem is, that whilst it gives some simplified information, it doesn't give women the whole picture. There's not enough information to make in informed choice.

The NHS breast screening program was introduced in 1988 (strangely at the same time as cervical screening was introduced, which is an interesting coincidence).

How has the incidence of breast cancer changed since it was introduced?

Let's have a look at the data:

So screening doesn't affect how many women get breast cancer, as it can't look for "pre-cancerous" cells, it can only detect cancer once it has developed to some degree. It doesn't stop you from getting breast cancer.

So what was the effect on mortality from breast cancer? Does finding it early increase your chance of survival?

(Source: Cancer Research UK)

Ok, so the short answer is yes. After 1988 there is a clear drop in the number of women dying from breast cancer. It looks impressive as a graph, but let's look at the absolute risk of dying from breast cancer.

Around 1988, 60 women per 100,000 were dying of breast cancer. That's a 0.06% risk. By 2016, that risk has declined to ~34 women per 100,000. That's a 0.034% risk. So the actual decline in risk is 0.026%.

The decline is of course due to early detection and treatment, so what's the harm?!

That is, of course, a good question.

As you'll see in my earlier posts, all screening tests have a sensitivity level, and a specificity level. These numbers indicate the chance of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives.

Instead of crunching the numbers myself, I'll post a figure from a respected medical journal:

(Source: https://breast-cancer-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13058-015-0525-z#Fig1)

So this shows that for every 1000 women screened over the course of 20 years, 200 will be incorrectly told that they have breast cancer, of those 200, 20 will also have a biopsy to rule out cancer.

3 will develop cancer anyway, either because it was missed in the mammogram, or a fast growing tumour grew between screening periods enough to cause symptoms (interval cancers). A previously negative mammogram might also cause women to assume they're "safe" and ignore symptoms.

15 out of the 1000 women will actually be treated for cancer that they don't have, with lumpectomy, mastectomy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy etc.

Only 2 breast cancer deaths will be prevented per 1000 women, but overall no deaths will be prevented. Why? Treating breast cancer, can cause other issues like heart problems, and you're killed by the treatment.

Another issue is that of finding cancers that, whilst definitely cancers, wouldn't cause you problems in your lifetime.

This is especially true for older women who would likely die from another condition (heart disease etc.) long before their breast cancer would kill them.

So, should you get screened? As always, it's your choice!

Inform yourself of the benefits, and risks, and make the decision based on your own personal situation.

The problem is, that whilst it gives some simplified information, it doesn't give women the whole picture. There's not enough information to make in informed choice.

The NHS breast screening program was introduced in 1988 (strangely at the same time as cervical screening was introduced, which is an interesting coincidence).

How has the incidence of breast cancer changed since it was introduced?

Let's have a look at the data:

So screening doesn't affect how many women get breast cancer, as it can't look for "pre-cancerous" cells, it can only detect cancer once it has developed to some degree. It doesn't stop you from getting breast cancer.

So what was the effect on mortality from breast cancer? Does finding it early increase your chance of survival?

Ok, so the short answer is yes. After 1988 there is a clear drop in the number of women dying from breast cancer. It looks impressive as a graph, but let's look at the absolute risk of dying from breast cancer.

Around 1988, 60 women per 100,000 were dying of breast cancer. That's a 0.06% risk. By 2016, that risk has declined to ~34 women per 100,000. That's a 0.034% risk. So the actual decline in risk is 0.026%.

The decline is of course due to early detection and treatment, so what's the harm?!

That is, of course, a good question.

As you'll see in my earlier posts, all screening tests have a sensitivity level, and a specificity level. These numbers indicate the chance of true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives.

Instead of crunching the numbers myself, I'll post a figure from a respected medical journal:

(Source: https://breast-cancer-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13058-015-0525-z#Fig1)

So this shows that for every 1000 women screened over the course of 20 years, 200 will be incorrectly told that they have breast cancer, of those 200, 20 will also have a biopsy to rule out cancer.

3 will develop cancer anyway, either because it was missed in the mammogram, or a fast growing tumour grew between screening periods enough to cause symptoms (interval cancers). A previously negative mammogram might also cause women to assume they're "safe" and ignore symptoms.

15 out of the 1000 women will actually be treated for cancer that they don't have, with lumpectomy, mastectomy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy etc.

Only 2 breast cancer deaths will be prevented per 1000 women, but overall no deaths will be prevented. Why? Treating breast cancer, can cause other issues like heart problems, and you're killed by the treatment.

Another issue is that of finding cancers that, whilst definitely cancers, wouldn't cause you problems in your lifetime.

This is especially true for older women who would likely die from another condition (heart disease etc.) long before their breast cancer would kill them.

So, should you get screened? As always, it's your choice!

Inform yourself of the benefits, and risks, and make the decision based on your own personal situation.

Tuesday, 4 December 2018

Survivor Fever

Survivor Fever. Yes, I made up the name; it seemed to fit.

What am I talking about?

Well, it's a phenomenon that happens all to often in screening.

Let's say that you go for a screening test, and you get back a negative result. You're happy, relieved, and want others to also be screened, to know that they're also "safe".

Then there are those that receive a positive result. Abnormal cells, we'd better act now. So they get their abnormal cells treated, which probably wasn't necessary (see previous posts), but now they feel that they had a lucky escape; evaded cancer. And so they become vehement advocates for screening; "It could save your life! It saved mine!".

The reality is that screening, whilst it can detect a proportion of cancer, or precancerous conditions, falsely diagnoses a magnitude more, and that, in itself, leads to a large population of people believing that screening is "important".

These people, due to the failings of both government, and charities, are not fully informed of the risks, benefits, and harms of screening. In fact, some of the loudest proponents of screening are those that have been harmed. People with minor, harmless, changes to their cells, that are treated needlessly, who end up thinking that they have been saved from cancer.

We all need to educate ourselves, read the numbers, make an informed decision, and not follow blindly like lemmings off a cliff.

What am I talking about?

Well, it's a phenomenon that happens all to often in screening.

Let's say that you go for a screening test, and you get back a negative result. You're happy, relieved, and want others to also be screened, to know that they're also "safe".

Then there are those that receive a positive result. Abnormal cells, we'd better act now. So they get their abnormal cells treated, which probably wasn't necessary (see previous posts), but now they feel that they had a lucky escape; evaded cancer. And so they become vehement advocates for screening; "It could save your life! It saved mine!".

The reality is that screening, whilst it can detect a proportion of cancer, or precancerous conditions, falsely diagnoses a magnitude more, and that, in itself, leads to a large population of people believing that screening is "important".

These people, due to the failings of both government, and charities, are not fully informed of the risks, benefits, and harms of screening. In fact, some of the loudest proponents of screening are those that have been harmed. People with minor, harmless, changes to their cells, that are treated needlessly, who end up thinking that they have been saved from cancer.

We all need to educate ourselves, read the numbers, make an informed decision, and not follow blindly like lemmings off a cliff.

Monday, 3 December 2018

Cervical Screening – Helping You Decide

Sounds familiar, right? It’s the title of the little green

information leaflet that is sent out with your invitation to attend cervical

screening. Let’s look at that. It’s an invitation, and you can decide whether

to take part or not. It’s a choice.

How do you make that choice? Well the leaflet has some

information in it, but not all the information we need to make an informed

decision, as you’ll know from previous posts on this blog. Let’s take a look at

the numbers.

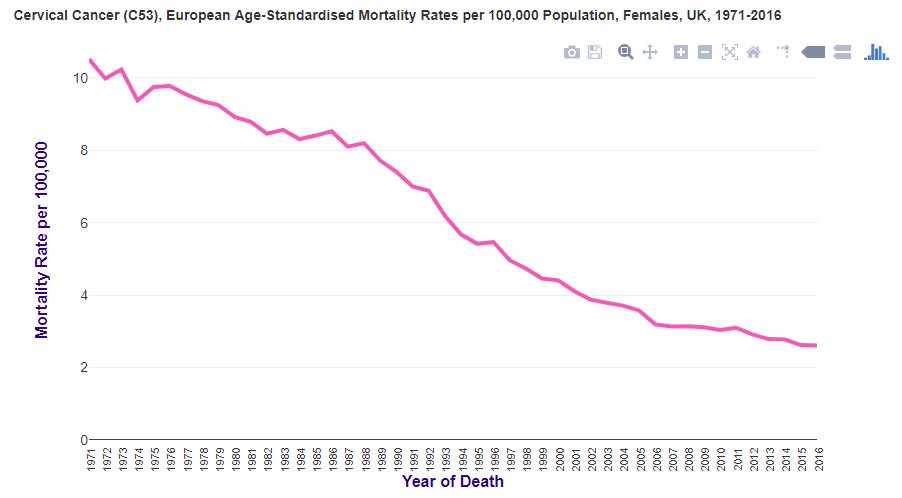

Organised cervical screening was introduced in the UK in 1988.

Mortality rates for cervical cancer were already in decline before that. Let’s

see how the screening test reduced cervical cancer deaths (source: Cancer

Research UK):

Well, I suppose it went down a little bit faster, but it was

already going down. Not a very dramatic change is it?

Why is that?

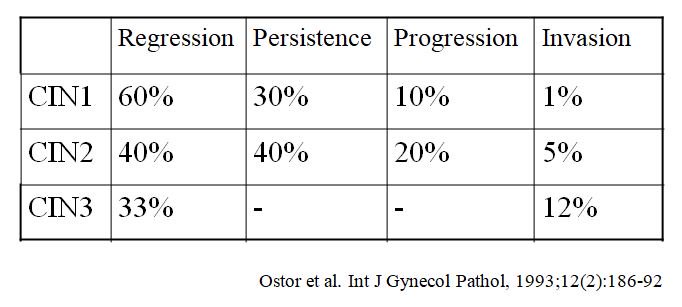

Cervical screening isn’t, as the leaflet agrees, a test for

cancer. It is a test for abnormal cells that might, just might, become cancer.

If you have abnormal cells detected with screening, you’ll likely worry, but

let’s look at how likely those cells are to become cancer (invasion):

Ok, so now we can breathe a sigh of relief, well, depending

on how abnormal our cells were. This is expressed as the CIN level, ranging

from 1 to 3. CIN stands for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. It’s not

cancer, but sometimes these cells can change into cancer. In the table above,

you can see how likely this is to happen, in the “invasion” column – this is the

risk of the cells becoming cancer.

So these abnormal cells that they’re looking for don’t

always become cancer. In fact, looking at the table above, it’s actually quite unusual

for this to happen.

What causes these abnormal cells, which might go on to cause

cervical cancer? The answer is HPV (source: https://embryo.asu.edu/pages/harald-zur-hausens-experiments-human-papillomavirus-causing-cervical-cancer-1976-1987).

HPV, or human papillomavirus, is a common virus, with many subtypes. Some cause genital warts, whereas others can

cause abnormal cells, which may become cancerous. HPV subtypes 16 and 18 are

the primary causes of cervical cancer. These HPV subtypes can be prevented with

vaccination. HPV is sexually transmitted, from penetrative sex, and also oral

sex. It is also implicated in cancers of the mouth, throat, penis and anus.

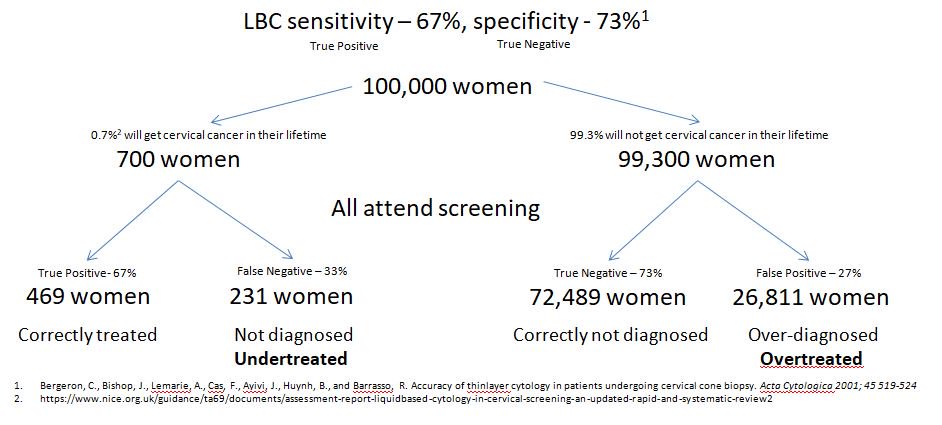

Anyway, how accurate is cervical screening?

In a previous post on this blog, we looked at sensitivity,

and specificity. Let’s see what that looks like for cervical screening:

LBC stands for liquid based cytology, and is the most up-to-date

method to collect smears. As we can see from this diagram, screening would

wrongly tell 231 women with cancer, that they don’t have it. It would also tell

26,811 women with no disease, that they have cancer.

This is a simplified diagram, as it only takes women with

actual cancer into account, not all those abnormal cells (CIN1, 2 & 3)

mentioned earlier. If we factored those in, given that up to 7.7% of women

might have abnormal cells at any one time (source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24305750),

that’s another 7,700 women that could be given false negative, or false

positive result. Even though those cells only have a small chance of becoming

cancer. This could result in treatment that women don’t need.

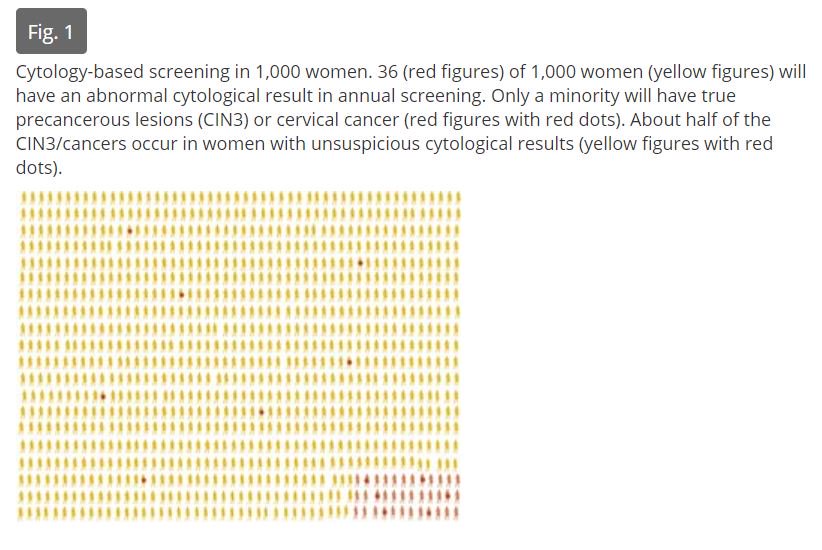

So what does this look like?

It’s a little hard to see, but when a smear test is read,

and the result sent back, of the 36 women with high-grade abnormal cells, or

cancer, detected, only 6 of those 36 will actually

have high-grade abnormal cells, or cancer. The rest do not. Of the remaining 964 women told that

they are fine, 7 of them will actually

have high-grade abnormal cells, or cancer, and be told that they don’t. It’s a

bit like flipping a coin for a correct diagnosis.

What about those women without abnormal cells, who are told

that they have abnormal cells, or cancer, erroneously?

Let’s take a look at that:

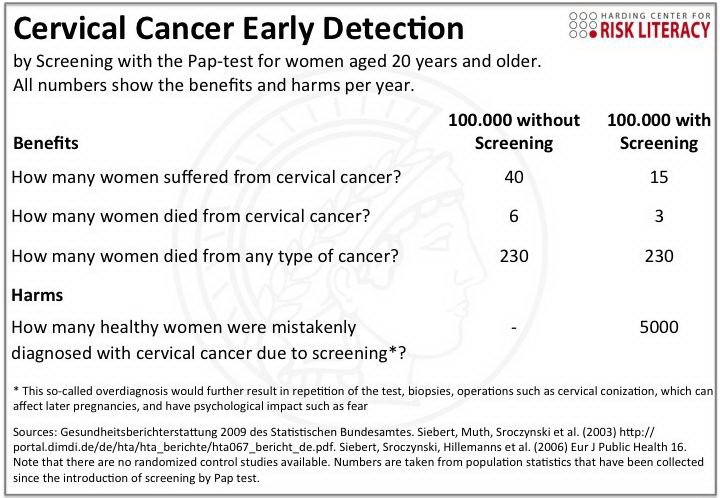

Without screening 6 per 100,000 women will die from cervical

cancer (0.006%), with screening 3 per 100,000 women will die from cervical cancer

(0.003%). This is a 50% relative

risk reduction, but really the actual risk

reduction is 0.003% (0.006% - 0.0003%)

However, with screening, 15 women would still develop cervical cancer, and 5000 women (5%) would be diagnosed with cancer

incorrectly, and treated.

So, what’s the problem with treating those 5000 women

incorrectly? What’s the harm?

CIN, and cervical cancer have different treatments. Cervical

cancer treatment might result in a hysterectomy, the removal of the uterus,

leaving women infertile, but could well save their lives. Cervical cancer

should be treated, as it can spread.

CIN treatment aims to remove the abnormal cells before they

become cancer (remember the risk of this happening from above). Such treatments

are LLETZ (Large loop excision of the transformation zone), Cone biopsy, Laser

therapy, Cold coagulation (it’s not cold, it’s actually very hot!), and Cryotherapy

(this one is actually cold). The aim of these treatments is to remove the

abnormal cells from the cervix.

Whilst not everyone suffers from side effects from these

treatments, there is always a risk of death from a general anaesthesia (if

required) which is 1 per 100,000 patients (source: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/general-anaesthesia/),

along with pain, bleeding and discharge.

Some treatments can cause cervical stenosis, where the

cervix becomes tightly closed, prevent sperm from reaching the uterus, and

fallopian tubes, causing infertility. Conversely, some treatments can cause weakening

of the cervix, which is a muscle, increasing the risk of preterm birth. (Source:

https://www.macmillan.org.uk/information-and-support/diagnosing/how-cancers-are-diagnosed/cervical-screening/treating-cin.html#3817)

So, should you get screened for cervical cancer?

The answer

is, it’s your choice. Being armed with all the relevant facts should allow you

to make your own decision, based on your own personal situation, as to whether you

wish to participate, or not.

Don’t be bullied into it by friends or doctors, make your

own, informed, choice.

Sunday, 2 December 2018

What's the harm in screening?

What's the harm in screening? That's a good question, let's look at it.

For this, we need to understand the concept of sensitivity and specificity.

They're confusing words, so I'll explain. Sensitivity is the measure of a test, expressed as a percentage, that shows how accurate it is at detecting a disease. So if I have disease A, and the sensitivity is 100%, then the test will definitely identify that I have disease A. If it is less than 100%, then there's a chance that it would miss the fact that I have disease A. This is called a false negative. Sensitivity of 60%, means that it will miss 40% of disease A cases.

Specificity is the measure of a test to only detect disease A. If the specificity is 100%, and I don't have disease A, then I can be 100% confident that that result is correct. However, if the specificity is less than 100%, then I might be told that I have disease A, when actually I don't. This is called a false positive. Specificity of 60% means that 40% of those tested will be incorrectly diagnosed with disease A.

So, here are the harms of screening. Being told that you don't have disease A when you actually do, and therefore might ignore symptoms of disease A thinking that you're all clear. Or, being told that you do have disease A, when you don't, resulting in treatment that you didn't need, the side effects of that treatment, and the worry and anxiety that goes along with it.

In reality no screening test has a sensitivity and/or specificity of 100%, so there are always false negatives, and false positives.

What we can do is understand these risks, enabling us to make an informed choice as to whether we want to participate in the screening program. Fully armed with the knowledge that we could be underdiagnosed, or overdiagnosed. Undertreated, or overtreated.

For this, we need to understand the concept of sensitivity and specificity.

They're confusing words, so I'll explain. Sensitivity is the measure of a test, expressed as a percentage, that shows how accurate it is at detecting a disease. So if I have disease A, and the sensitivity is 100%, then the test will definitely identify that I have disease A. If it is less than 100%, then there's a chance that it would miss the fact that I have disease A. This is called a false negative. Sensitivity of 60%, means that it will miss 40% of disease A cases.

Specificity is the measure of a test to only detect disease A. If the specificity is 100%, and I don't have disease A, then I can be 100% confident that that result is correct. However, if the specificity is less than 100%, then I might be told that I have disease A, when actually I don't. This is called a false positive. Specificity of 60% means that 40% of those tested will be incorrectly diagnosed with disease A.

So, here are the harms of screening. Being told that you don't have disease A when you actually do, and therefore might ignore symptoms of disease A thinking that you're all clear. Or, being told that you do have disease A, when you don't, resulting in treatment that you didn't need, the side effects of that treatment, and the worry and anxiety that goes along with it.

In reality no screening test has a sensitivity and/or specificity of 100%, so there are always false negatives, and false positives.

What we can do is understand these risks, enabling us to make an informed choice as to whether we want to participate in the screening program. Fully armed with the knowledge that we could be underdiagnosed, or overdiagnosed. Undertreated, or overtreated.

Relative risk, versus Actual risk

If you've ever read the Daily Mail, you'll likely have seen headlines such as "Eating food A can reduce your risk of cancer B by 50%".

Let's look at that. If my lifetime chance of cancer B was 5 cases per 10 people, and it was reduced by 50%, it would be reduced to 2.5 cases per 10 people (2.5 is half of 5). Before the risk was 50% ((5/10)*100), and eating food A reduced it to 25% ((2.5/10)*100) - Great, right?

However the above example illustrates a situation when the relative risk, aligns to the actual risk. This is rarely the case in reality.

What if my lifetime chance of cancer B was only 1 case per 1,000,000 people? Eating food A would reduce my risk of cancer B by 50% to 0.5 cases per 1,000,000 people (50% of 1).

Before my actual risk of cancer B, expressed as a percentage would be ((1/1,000,000)*100), which is 0.0001%. After my risk of cancer B would be halved to 0.00005%. So my actual risk reduction is only 0.00005% (0.0001 - 0.00005) compared to what is was before, despite my risk having halved by 50%.

So, without knowing the actual original lifetime risk, you cannot know how much your actual risk of a disease decreases for any form of screening or procedure.

Let's look at that. If my lifetime chance of cancer B was 5 cases per 10 people, and it was reduced by 50%, it would be reduced to 2.5 cases per 10 people (2.5 is half of 5). Before the risk was 50% ((5/10)*100), and eating food A reduced it to 25% ((2.5/10)*100) - Great, right?

However the above example illustrates a situation when the relative risk, aligns to the actual risk. This is rarely the case in reality.

What if my lifetime chance of cancer B was only 1 case per 1,000,000 people? Eating food A would reduce my risk of cancer B by 50% to 0.5 cases per 1,000,000 people (50% of 1).

Before my actual risk of cancer B, expressed as a percentage would be ((1/1,000,000)*100), which is 0.0001%. After my risk of cancer B would be halved to 0.00005%. So my actual risk reduction is only 0.00005% (0.0001 - 0.00005) compared to what is was before, despite my risk having halved by 50%.

So, without knowing the actual original lifetime risk, you cannot know how much your actual risk of a disease decreases for any form of screening or procedure.

The issue of informed consent

Many of us will have had a letter through the letterbox, "inviting" us to attend screening for cancer. Be it Cervical cancer, Breast cancer, Bowel cancer etc.

What's clear to me from these letters, and their accompanying information leaflets, is that we are not being given clear, impartial advice on which to make an informed decision.

They use headline statements like "5000 lives saved!", but don't tell you your actual risk of developing the disease, or the likelihood that you could be overdiagnosed, and overtreated, resulting in potential harm, both physically, and mentally.

So, what is necessary to make an informed decision? Firstly we should know what the risk of the disease would be, if we didn't choose to be screened. Secondly, we should know the risk of the disease, if we did choose to be screened. Thirdly, we should know the risk of being treated for a disease that we never actually had, or precancerous conditions that may not have gone on to cause disease.

Another point to consider, is all-cause mortality. For example, if 100,000 people are screened for disease A, and 20 cases of disease A are treated successfully, what are the chances that those 20 people would actually die from disease B, C, or D, in the same timeframe as they would have from disease A?

To illustrate this, if we screened women aged 80-90 for breast cancer, and picked up 3 cases, and treated them, how many of those 3 women would live beyond 90 anyway, without dying from another condition?

To make an informed decision, we need facts, evidence, and information to enable us to understand our individual risk. Most of the information provided to the public does not achieve this, and instead appears to encourage people to participate, giving a sense of risk in not doing so. We'll look into that later.

Screening relies on getting "people through the door". It relies on healthy people at little risk of disease submitting to screening, in order to find the few that do get the disease. The "needles in the haystack".

What's clear to me from these letters, and their accompanying information leaflets, is that we are not being given clear, impartial advice on which to make an informed decision.

They use headline statements like "5000 lives saved!", but don't tell you your actual risk of developing the disease, or the likelihood that you could be overdiagnosed, and overtreated, resulting in potential harm, both physically, and mentally.

So, what is necessary to make an informed decision? Firstly we should know what the risk of the disease would be, if we didn't choose to be screened. Secondly, we should know the risk of the disease, if we did choose to be screened. Thirdly, we should know the risk of being treated for a disease that we never actually had, or precancerous conditions that may not have gone on to cause disease.

Another point to consider, is all-cause mortality. For example, if 100,000 people are screened for disease A, and 20 cases of disease A are treated successfully, what are the chances that those 20 people would actually die from disease B, C, or D, in the same timeframe as they would have from disease A?

To illustrate this, if we screened women aged 80-90 for breast cancer, and picked up 3 cases, and treated them, how many of those 3 women would live beyond 90 anyway, without dying from another condition?

To make an informed decision, we need facts, evidence, and information to enable us to understand our individual risk. Most of the information provided to the public does not achieve this, and instead appears to encourage people to participate, giving a sense of risk in not doing so. We'll look into that later.

Screening relies on getting "people through the door". It relies on healthy people at little risk of disease submitting to screening, in order to find the few that do get the disease. The "needles in the haystack".

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Still confused about cancer screening, and whether it's right for you?

Still confused about cancer screening, and whether it's right for you? I've posted a lot of information in this blog, some of it m...

-

If you've made an informed choice to participate in cervical screening, then it's likely at some point that you'll have an ...

-

It quite a nice pink leaflet really, despite what's inside. The problem is, that whilst it gives some simplified information, it doesn...

-

Sounds familiar, right? It’s the title of the little green information leaflet that is sent out with your invitation to attend cervical sc...